Abandoned History

Although as a transportation hub, harbors are heavily used and modified over time, they too can be home to shipwrecks or ship graveyards. The seaport of Baltimore, Maryland is no exception to this. In addition to the wrecks located in both Curtis Bay and Curtis Creek (which will be discussed in a future blog post), there are the remains of the steamer Governor R.M. McLane located just outside the premises of the Baltimore Museum of Industry. Unlike the most conventional perception of a shipwreck which is an archaeological site created by a singular catastrophic event, wrecks like that of Governor R.M. McLane were simply abandoned by their owners and left behind to weather the elements. Much like a worn lithic flake tossed aside by an ancient flint knapper, ships would be used and worn down over time and when they outlive their usefulness, they would be cast aside typically in a quiet backwater away from main shipping channels. Sometimes when one ship would be abandoned and deposited in this way, others would abandon their ships in the same place creating what is known as a ship graveyard. The ship graveyard in Mallows Bay, on the Potomac River, is a prime example of this and it was recently made into an NOAA National Marine Sanctuary. Shipwrecks deposited this way are still history and still can teach us much. Although the wreck of Governor R.M. McLane is eminently accessible and is interpreted by the neighboring Baltimore Museum of Industry, much about this ship lies forgotten and this blog post serves to rectify that.

The Governor R.M. McLane

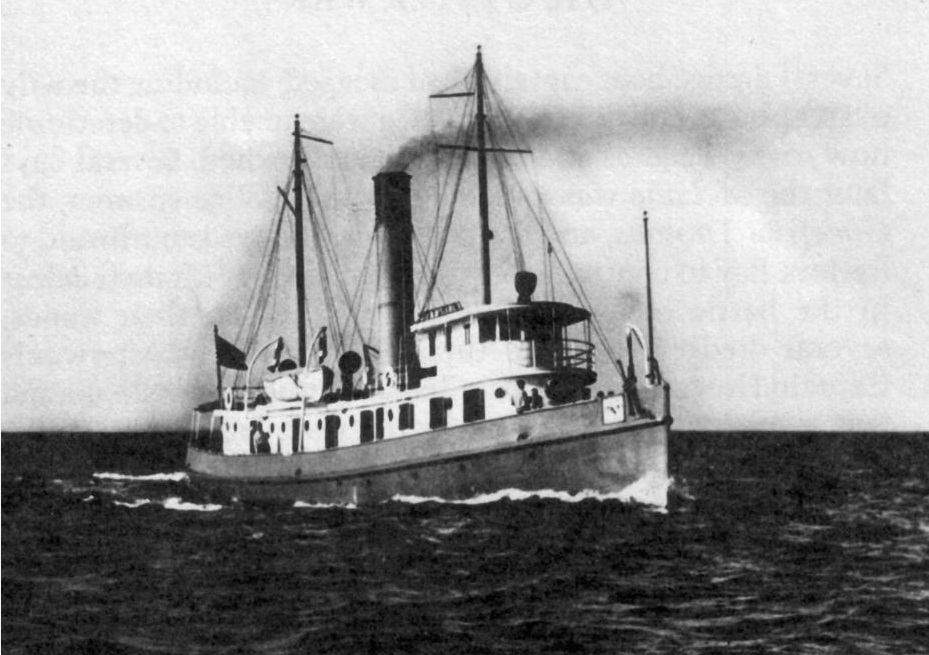

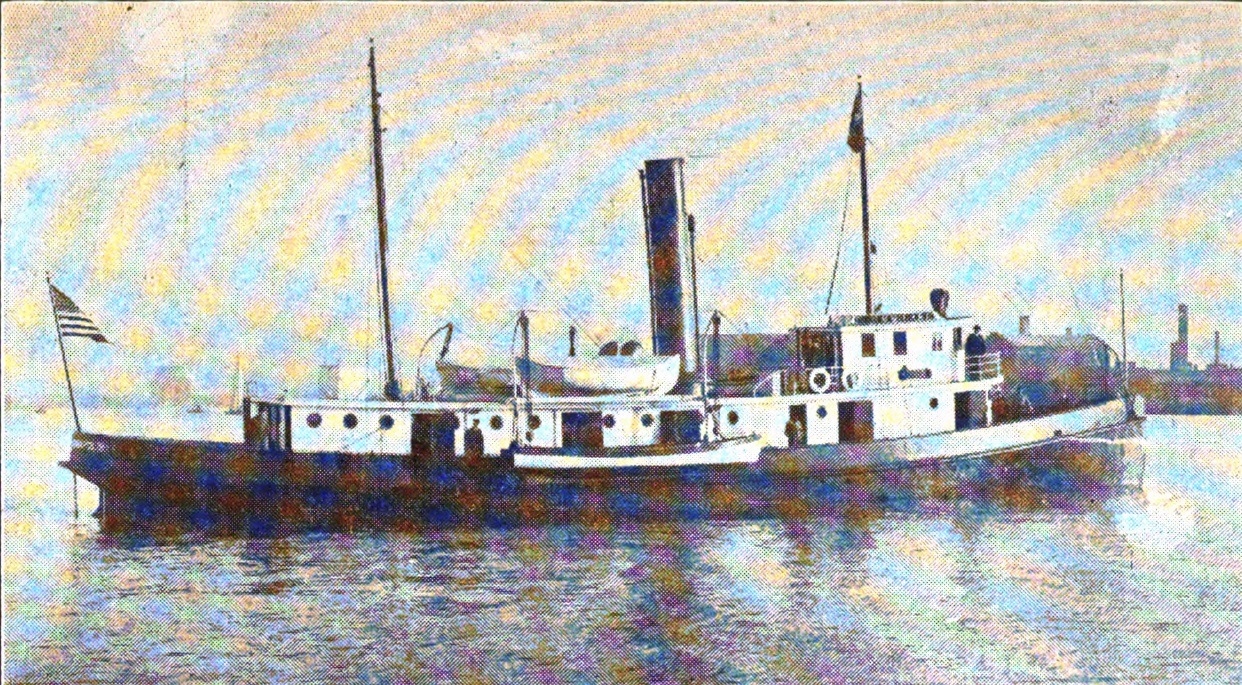

Governor R.M. McLane was built at the shipyards of Neafie and Levy in Philadelphia Pennsylvania in 1884. The vessel as built was 113 feet long, 21 feet wide, and weighs in at 144 tons, it was named for the then 39th Governor of Maryland, Robert Milligan McLane (1884-1885). The vessel was steam-powered turning a propeller. The McLane was built for Maryland’s nascent “Oyster Navy” or State Fishery Force to intercept, enforce and police illegal oyster dredging on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland waters. With its iron hull and a top speed of 13 knots (15 mph), the McLane was perfectly suited for its intended duty. Upon completion, the Governor R.M. McLane was made the flagship of the “Oyster Navy” and served in that capacity until 1931, replacing the aging iron-hulled sidewheel steamer Leila. The McLane was one of a pair of identical steamers built by Neafie & Levy for the Oyster Navy, the second being the Governor P.F. Thomas. The McLane would be armed variously throughout its career first with a 12-pound boat howitzer and second with a 1-pound gun.

“If I am a pirate, I was driven to it by the Authorities…” H.P. Cannon, Oyster Dredger, and “Pirate Chief”

The Maryland Oyster Wars

Oyster harvesting was a big business in the Chesapeake Bay and Oyster Canning became an important industry in Baltimore, Maryland. As early as 1820, it was realized that the overharvesting of oysters could become an issue. The first law enacted to preserve oysters prohibited all methods of oyster harvesting except the traditional method of hand tongs and oysters could only be exported by Maryland citizens. This law was created due to the fact that many oyster boats were sailing down to the Chesapeake Bay from the depleted oyster beds further north and then transport the oysters for sale in northern markets. In 1865 the law was amended to allow for dredging in offshore waters while setting aside the shallow waters and rivers for hand tonging. This allowed for larger harvests and larger payouts at the market. Oystermen needed a license and steam-powered vessels were prohibited. Enforcement of this law rested in the hands of local authorities and was spotty at best. Oyster canning became a booming industry for Baltimore during reconstruction. Canned oysters were a highly coveted status item that yielded huge profits for anyone associated with the industry. It was hard on the workers in both canneries and out in the oyster dredge boats. It became difficult for dredge boat captains to find crews willing to do the job, therefore they had to resort to more illicit methods to build crews by shanghaiing or kidnapping hapless bar patrons or unwitting immigrants into the region. This way, they did not have to pay these crews wages. The rivalry between canneries and oyster boats became so intense that there was fighting between them from open water to dockside. The Oyster boom of the late 1860s bred a culture of lawlessness on the Chesapeake bay that required intervention by authorities and in 1867 the Maryland State Fishery Force was established with the laughable goal of policing over 2,500 oyster boats including the Leila. The first commander of the Maryland State Fishery Force was a man named Hunter Davidson who during the Civil War had served with distinction in the Confederate Navy including as an officer aboard the CSS Virginia. Davidson made inroads to build the Oyster Navy; hiring officers, outfitting them, and their boats with weapons. He had also made a series of recommendations to the Maryland general assembly to protect and manage oysters; he felt that there needed to be at least a three-year moratorium on dredging because he believes the oyster population had been depleted to that degree, and recommended that there be no dredging at night (making it easier and safer for enforcement), seasonal restrictions on dredging, he advocated for high licensing fees on the oystermen to compensate for the lack of necessary resources law enforcement had available and lastly a tax per bushel of oysters in all persons engaged in the oyster industry. Davidson was not a popular man in both the government he represented and the outlaws he policed. In 1871 infamous oyster pirate Gus Rice (we’ll see more of him later) had gone as far as boarding the Leila at night and attempted to murder Davidson as he was sleeping in the captain’s cabin. Davidson had managed to drive off Rice and his accomplices with a pair of colt revolvers. Owing to his frustration between both the Oyster Dredged and ineffective judges he left the service in 1872. As Davidson had predicted, the oyster harvests began to dwindle throughout the 1870s which drove both dredge captains and canneries to scramble to maintain the profits they had seen. The Oyster Navy came under the auspices of another former confederate naval officer, James Waddell, former Captain of the confederate raider CSS Shenandoah. Who better to fight pirates than a former pirate himself. Under Waddell, enforcement of oyster laws became more rigorous, he was the one who authorizes the construction of both the McLane, the Thomas, and a wooden-hulled steamboat Governor Hamilton in 1882 to help bolster the Oyster Navy. During this time, the canning industry fought a constant political battle to weaken the authority of the fisheries force while the bad descended into further lawlessness. While construction on the McLane was nearing completion in 1884, the oyster pirates had grown bolder while the Oyster Navy proved ineffective to combat them. One of the last captures of the Leila was the crew and dredger Maud Miller, its captain Sylvester Cannon had managed to escape. The Leila had towed the vessel into Goose Creek to be turned over to local Justice Robinson to be impounded. Sylvester’s father H.P. Cannon had strode aboard the Leila wearing a belt with four loaded revolvers. H.P. Cannon had one time himself been a civil magistrate and knew the laws well and he was able to parley with Justice Robinson that the seizure of his son’s boat was unlawful as his son was not aboard when it was captured. Justice Robinson relented and agreed to the accuracy of the law and released the Maude Miller to H.P. Cannon. As his father sailed away with his boat, Sylvester hiding on shore opened fire on the Leila causing them to launch a boat to shore to combat and perhaps capture him. When his pursuers landed their boat, Sylvester took off into the nearby woods and made his way to the home of Justice Robinson, where he broke in and threatened his family, and claimed that he would find and kill Robinson. He left to go find the Justice, meanwhile, his family ran to get help from neighbors, Sylvester returned to find several armed men, meanwhile, the landed crew of the Leila had caught up and managed to fire at Sylvester as he once again escaped into the woods. This story is one of many similar stories during the Oyster War.

“Bivalve Buccaneers” & the Corsica Incident

This came to a head late in 1888 in what became the most decisive conflict in the course of the Maryland Oyster Wars. On 8 November 1888, the police sloop Eliza Hayward hailed a small fleet of pirate dredgers operating in the Little Choptank River and opened fire with its cannon when they failed to respond and disperse. The pirate dredges then surrounded the sloop and opened fire, though the Eliza Hayward and its crew managed to escape to Oxford, Maryland. The new fishery vessel Governor R.M. McLane was dispatched to the area and the pirates dispersed ahead of its arrival only to return after the McLane departed the area. During this time, the oyster pirate Gus Rice rose to prominence and was widely regarded as a “Pirate Chief” in the media, he was the acknowledged leader of the illegal oyster boats operating out of the Chester River on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. On 27 November 1888, Gus had made a fatal error, hearing rumors of the Maryland Oyster Navy’s new steamers, he had mistakenly opened fire on the steamboat Corsica of the Chester River Steamboat Company while making its typical run to Baltimore. As the Corsica neared the mouth of the Chester River, it grew foggy where it encountered Rice’s fleet of pirate dredges at work. The crews of the pirate dredges began yelling at the passing steamer and someone on the steamer made the mistake of whooping back at them. Obscured by fog, the Corsica was mistaken for an oyster navy steamer and the entire fleet of pirate dredges opened fire on the unarmed passenger steamer carrying women and children aboard.

Fortunately, Corsica managed to continue onward to Baltimore and no one aboard was injured in the conflict. The incident had caused widespread outrage and indignation across the state, the oyster pirates had lost all sympathy. The governor of Maryland ordered Governor R.M. McLane dispatched to the Chester River to engage Gus Rice and his pirate band. The McLane was in Annapolis having a 12-pound boat howitzer installed on its deck. Due to the severity of the situation, the McLane got underway while carpenters were still working on installing the howitzer. The McLane was then captained by Thomas C.B. Howard, a former oysterman himself, he had joined the oyster navy because he purely felt like it was his duty. Howard and his first mate Oliver Crowder also had iron plate attached around the base of the pilothouse for protection. When in battle, Crowder could remove the compass binnacle and pilot the McLane while sitting on the deck protected by the armor.

The McLane arrived at the mouth of the Chester River on the night of 10 December 1888 where a fleet of 70 pirate dredges were at work. Gus had set two outlying dredges to act as sentinels. Captain Howard and two of his crew got into McLane’s skiff and silently captured both of the sentinel dredges and their crews. After capturing the second dredge, the skiff and the McLane were both spotted and the alarm went out across the collected pirate dredges. Howard sped the skiff back to the steamer, meanwhile, the pirate dredges began to disperse, however, the wind was blowing downstream the Chester River and the dredges had to tack back and forth to maneuver upstream. This made the dredges easy targets for McLane’s howitzer, The pirate chief Gus Rice had planned for this, he had lashed together a raft of a dozen dredge boats with a chain that was quickly drifting downstream with the current. The upper decks of each of the dredges on this raft were fortified with large iron plates.

“Join me boys in victory or in hell!” Gus Rice, Pirate Chief

Thirty pirates proceeded to open fire on the McLane from behind the iron plates on their raft. In return, the McLane fired off four shots from its howitzer, each passing through the rigging of the makeshift raft bearing down on them. The McLane was too close to depress its gun any lower to fire and the raft was so well fortified that neither rife nor the howitzer had any effect on the pirates. Captain Howard then ordered the McLane to turn toward the raft and ordered full ahead and rammed its iron hull into the wooden pirate dredge Julia H. Jones taking the full brunt and was damaged in the stern all the way to the companionway. One of the pirate crew had fallen onto the deck of the McLane and was captured. The gunner at the howitzer was brought down by a bullet through his arm. Howard then ordered the McLane into full reverse and then full forward again to ram into the raft this time directly into the stern of Rice’s flagship the dredge J.C. Mahoney. As this last ram lodged the McLane into the center of the fortified raft, the crew began to open fire at the now exposed pirates. With two of the dredges on the raft sinking and their iron plates rendered ineffective, the rest of the dredges still attached began to cast themselves off and disperse along with the rest of the pirate dredges. Gus Rice was able to escape into history, after this battle, there is nothing further mentioned of him. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to the crew of the McLane there was shanghaied crew trapped inside both of the sinking pirate dredges, unable to escape, they went down with the pirate dredges. The McLane was later joined in the Chester River by its sister the Thomas. The two steamers then patrolled southward in an attempt to find Rice and his fleeing fleet of pirate dredges, where a few days later they encountered a fleet on Easton Bay and the crews apparently surrendered. The Oyster Navy and Governor McLane had won its first victory and in light of this, many oyster pirates beached their boats and ran but the conflict was by no means over. Both steamers returned to Annapolis to a hero’s welcome. Later on 27 December 1888 the oyster navy sloop Julia C. Hamilton discovered a fleet of illegal dredgers operating offshore and ordered them away. As they sailed away the schooner was enveloped in a dense fog where the pirate dredges returned and Captain Tyler engaged them in an hours-long battle that resulted in over 600 shots being fired, with no one injured.

The next day the McLane steamed to reinforce the Hamilton which captured five pirate dredgers and towed them to Cambridge, Mayland. As effective as these steamers were, they were only two versus multiple adversaries and they could not be everywhere in the bay at once.

Potomac Border Patrols

After their victory both the McLane and Thomas were sent to patrol the Potomac River and safeguard Maryland shipping on the river partially due to the fact that in 1889 Virginia passed a law that allowed private leasing of oyster flats, however, the problem was that at this time the boundary between Virginia on both the Potomac and on the Chesapeake was still vague and unclear. These leased flats could very well have been in Maryland waters. In 1890 the Virginia legislature authorized the creation of its own oyster navy of four vessels but their duty was more to keep Maryland pirate dredgers out of their waters. Dredgers of both states and the authorities of both states fought each other. In 1892 Governor McLane conducted another patrol of the Potomac this time with a U.S. Marshall and a representative of the Baltimore German Society aboard. Most of the immigrants being shanghaied into the pirate oyster force were German and as such, the German society had a vested interest in trying to intervene and save these hapless people. The McLane patrolled to Potomac seeking a dredge that had kidnapped fourteen newly arrived immigrants and had captured the dredge Partnership and arrested its Captain Stewart Evans and rescued the immigrants trapped aboard. They had held these immigrants for two months. Later that same week, the McLane rescued immigrants left abandoned aboard the icebound dredge Viola without any food or water. The use of a state-owned vessel had angered the powers that be in the oyster industry and the Baltimore Oyster Exchange had lobbied and protested with the Governor of Maryland to have the law amended to make it ineffective. The border dispute between Virginia and Maryland continued into 1894 where the fighting along the Annemessex River was so intense that the governor of Maryland continued keeping both the McLane and Thomas patrolling the Potomac River.

World War I Service

The Maryland Oyster War began to wind down at the beginning of the 20th century, with the technological innovation of gasoline diminishing the need for labor bet it forced or otherwise hauling dredges and the passing of several laws in the US making the practice of shanghaiing illegal. Governor R.M. Mclane would settle into the duties that it was meant for, surveying natural oyster beds and bottoms that could be suitable for the culture and development of new oyster beds. Both Governor R. M. Mclane and Governor P.F. Thomas required extensive repairs and over the years of 1904-1905, both were repaired with Governor Thomas receiving almost an entirely new hull. Later in 1905 Governor McLane had collided and sunk the dredge Eva Hemmingway and its owners sought restitution for their loss by the state. On 21 July 1916, the first meeting between the Maryland Commission and Virginia authorities took place aboard Governor R.M. McLane on the Potomac to agree on uniform rules to be enforced between both states and end the conflict. This led to a second meeting on 16 August 1917 that included representatives from the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and U.S. engineers for Norfolk and Washington to continue cooperation between the two states and ensure uniform law on the Potomac River was also held aboard Governor R.M. McLane. It became standard to hold these meetings between the two states aboard Governor McLane. In 1917 the oyster navy or oyster police force was integrated into the Maryland State Fishery Force and managed by the Conservation Commission of Maryland. The U.S. Navy was bereft of boats and ships at the outset of WWI, due to this the U.S. Navy approached the Conservation Commission of Maryland and proposed that the commission boats like the McLane be used to maintain local patrols for the Navy. The Maryland legislature agreed with this proposal provided that the state force become part of the U.S. Naval Reserves and conduct the same fishery patrols and all expenses in crew and ship maintenance would be financed by the Navy. Governor Mclane was armed with a singular 1-pound gun given the designation Navy designation of SP-1328 and began its US Navy patrols in August 1917. The McLane was the flagship of Squadron 8 of the 5th naval district with Ensign S. Earle in command.

The USS Governor McLane patrolled the Chesapeake, Baltimore Harbor, Patuxent River, Severn River, and the Tangier Sound. Its sister the Governor P.F. Thomas was sold in 1917, it is unknown what became of the vessel. In November 1918 the McLane was briefly used as a towboat by Indian Head Naval Proving Ground. The McLane along with the rest of the boats of the Conservation Commission was returned to the state of Maryland on 30 November 1918. At which point the Commission began modernizing its fleet including the McLane in the summer of 1919. McLane had its steam engine repaired and received a new engine bed at Spedden Shipbuilding. Work on the McLane was nearly complete when the steamer was nearly destroyed by a fire while moored at the Piers of Canton Lumber Company adjacent to Spedden Shipbuilding (located in Fells Point, Baltimore at roughly 1707 Thames Street) where the steamer was waiting to be inspected. The Maryland Conservation Commission had the burnt hull of McLane surveyed where it was determined to be salvageable and had the vessel rebuilt with $35,000 from insurance. While the McLane was being rebuilt the navy had lent its patrol vessel USS Hiawatha (SP-183) as its replacement. Governor R.M. McLane was repaired and rebuilt at Spedden Shipbuilding Company and was completed on 10 November 1920. When completed, it was lengthened to 120 feet long and 22 feet in beam.

In 1921 Governor McLane was based in Cambridge, Maryland for further surveys of oyster beds and the planning of seeding new beds. As was the steamer had become the usual meeting place another meeting between representatives of the States of Maryland and Virginia were held aboard to discuss fishery problems of the Chesapeake Bay and pass further resolutions on 14 July 1923. In 1931 the McLane was replaced as the flagship of the Conservation Commission by the 135-foot steam yacht Tech. The McLane still continued in state service and in 1937 was based in Annapolis and conducted fishery patrols and inspection work on the Chesapeake Bay. In 1948 the 64-year-old Governor R.M. McLane was sold to George Curlett of Baltimore, Maryland where he had the vessel repowered with diesel engines where she continued to be used as a towboat around Baltimore and Solomons Maryland until 26 January 1954 when she was sold and abandoned at the yards of ship repair firm Hercules Company in the place where the wreck lies today. Apparently, the engines and superstructure were removed at some point after the vessel was abandoned.

The Wreck Today: Historic Preservation Done Right

The hull of Governor R.M. McLane was left abandoned where it is and over time, other small workboats and barges were abandoned around the dilapidated hull making a small shipwreck graveyard. The hull was surveyed archaeologically in 1994 due to an expansion on the Baltimore Museum of Industry. The museum had acquired the property that the hull is adjacent to and it was feared that future construction could affect possible historic resources. The BMI had planned a parking lot, promenade, and pavilion that were all eventually built around the wreck. A pier was additionally planned and that was moved next to the wreck. The hull was there but at that time its name had been forgotten to history. The wreck’s identity was now a mystery. How archaeologists were able to determine the identity of the wreck, they measured the hull at 120 feet long. Aerial photographs taken of Baltimore in 1964 and 1977 show what looked to be the hull therefore it was concluded that it has been there for some time. Much archival searching was conducted but ultimately archaeologists had climbed aboard the remains and they were able to find “NETTON 110” stamped into the stern which was McLane’s reported net tonnage and they were able to find “No. 234375” stamped on the starboard side which was McLane’s official registration number verified by the vessel’s U.S. Merchant Marine Papers. This is how archaeologists were able to positively identify the wreck. The hull appears to have capsized (or collapsed) and only the stern section still has deck planking attached. An underwater survey was conducted which found that underwater most of the iron hull is rusted through with intact iron ribs sticking out. The center had rusted out causing the hull to capsize and appear as it does today. As it was a vessel of historic significance, it is eligible for nomination into the National Register of Historic Places, but that never occurred. The current pier for the Baltimore downtown sailing club was built around the vessel and the parking lot for the BMI is just feet in front of it with a few signs giving the interpretation. Even though not officially listed on the NRHP, all the modern construction has been done around the wreck and the wreck was included in the plans for it to still be something that you can see and appreciate to this day.

The wreck was briefly threatened in 2001 due to the proposed construction of a Pier for the liberty ship John W. Brown, which was briefly being considered being moored and displayed at the BMI. Although John W. Brown was recently facing issues in finding a new home it was not seen as a good idea to sacrifice one historic property for another. Governor R.M. McLane doggedly persists after pirates, a fire, a world war, obsolescence, abandonment, and now time. This wreck has a rich, varied, history where it led conservation efforts and now it sits in stark contrast to the neon skyline of Baltimore Maryland a stark reminder of maritime history. If you want to visit the wreck of Governor McLane it is located on the grounds of the Baltimore Museum of Industry and Baltimore Downtown Sailing Center at 1415 Key Highway, Baltimore, Maryland 21230. It’s located just north of the Pavilion and the Parking lot.

“…Its remains serve as a symbol of historical precedence to claim roots in an industrial past. The existence of decaying ruins amplifies the age of industrial institutions and ground their symbolic meanings in a legitimate past. Decay secures antiquity. Ruins help to inspire reflections on institutions that had once been proud or strong.” Paul A. Shackel

Sources & Resources

Baltimore Museum of Industry

The Baltimore Sun. “Oyster Wars”. February 10, 2015

https://www.baltimoresun.com/bal-mptoyster-story.html

The Baltimore Sun. This Day in History: Aug. 5.

Burgess, Robert H. Chesapeake Circle.

Boston Daily Advertiser. The Most Decisive Conflict Yet Reported in the Course of the Maryland Oyster War. December 13, 1888

Cottom, Ric. Your Maryland: Little Known Histories from the Shores of the Chesapeake to the Foothills of the Allegheny Mountains.

Cottom, Ric & Morgan, Lisa. “Gus Rice”. WYPR.

https://www.wypr.org/post/gus-rice-1

Daily Dispatch. A Battle With Oyster-Pirates. February 9, 1884

Daily Inter-Ocean. A Naval Engagement. December 12, 1888

Ervin, Richard G. Archeological Evaluation and Archival Research Associated with the Harborwalk Southern Terminus, Property Acquisition at 1425-1435 Key Highway, Baltimore City, Maryland.

Englund, Will. Chesapeake Bay is Graveyard of Many a Ship Over Centuries Wrecks and Wreckage: 250-year-old Junkyard Cluttered with Debris Bespeaks a Long and Active Sailing History. The Baltimore Sun.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1995-10-14-1995287014-story.html

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. The Battle of Chester River. April 9, 1881

Goodall, Jamie L.H. Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay from the Colonial Era to the Oyster Wars.

Harper’s Weekly. The Oyster War. January 9. 1886

Heller, Michael. The Gridlock Economy: How Too Much Ownership Wrecks Market, Stops Innovation and Costs Lives.

The Historical Marker Database. Hull of the Gov. R.M. McLane Historical Marker.

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=131181

Langley, Susan. Governor Robert M. McLane Flagship of the State Oyster Police Force. TheBay.net

LeGrand, Marty. Lone Tree Opposite Shore. Chesapeake Bay Magazine.

https://chesapeakebaymagazine.com/lone-cedar-tree-opposite-shore/

Library of Congress. The Oyster War in Chesapeake Bay.

https://www.loc.gov/item/2002698357/

Martin, Pat Stille. E. James Tull, Shipbuilder on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Maryland Conservation Commission. Annual Report of the Conservation Commission of Maryland. Second Through Seventh.

Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Hunter Davidson: Fighting Naturalist.

https://news.maryland.gov/dnr/2018/03/30/fighting-naturalist/

Mountford, Ken. Chesapeake’s Oyster Reefs Shellacked by Years of Dredging. Bay Journal.

https://www.bayjournal.com/article/chesapeakes_oyster_reefs_shellacked_by_years_of_dredging

Maryland Fisheries. Maryland Fisheries Volume 2. 1931

Moale, H. Richard. Notebook on Shipwrecks Chesapeake Bay 1800-1977.

Mooney, James. Dictionary of American Fighting Ships Volume 3.

Navsource. Governor R. M. McLane (SP-1328)

http://www.navsource.org/archives/12/171328.htm

NOAA. Mallows Day-Potomac River National Marine Sanctuary

https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/mallows-potomac/

Pelton, Tom. A Forgotten Bay Veteran. Baltimore Sun.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2001-02-21-0102210384-story.html

Plummer, Norman H. Maryland’s Oyster Navy: The First Fifty Years.

Richards, Nathan. Ship’s Graveyards: Abandoned Watercraft and the Archaeological Site Formation Process.

Richards, Nathan. The Archaeology of Watercraft Abandonment.

Schaum, Jack. Lost Chester River Steamboats From Chestertown to Baltimore.

Schneider, Howard. In Winter of 1889, Oyster Wars Churned the Chesapeake. Washington Post.

Shipbuilding History. Neafie & Levy.

http://shipbuildinghistory.com/shipyards/19thcentury/neafie.htm

Shipbuilding History. Spedden Shipbuilding.

http://shipbuildinghistory.com/shipyards/small/spedden.htm

The New York Times. Piratical Oyster Crews. February 15, 1884

The New York Times. Chesapeake Pirates Routed. December 30, 1888

Strecker, Mike. Shanghaiing Sailors: A Maritime History of Forced Labor 1849-1915.

Wennersten, John. The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay.

Wisconsin State Register. Maryland’s Navy Vindicated. December 15, 1888

Wolfe, Kerry. The Notorious Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay. Atlas Obscura.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/oyster-pirates-of-chesapeake-bay

One thought on “Sunk in Baltimore Harbor, the Stalwart Governor R.M. McLane”