“Ships and boats are made to operate, they’re not made to sit around and be museum pieces…unless you’re the federal government with unlimited resources that can maintain the USS Constitution, it’s not feasible to maintain an “old ship.”” Bill Klein, St. Louis Marine

The Museum Ship That Never Was

The third ship in the museum ships series was never a museum ship per se, it was a unique historic vessel that never got the opportunity to be preserved, the SS Admiral. Admiral was a modern art deco western river steamboat that plied the Mississippi River around St. Louis, Missouri. Admiral was an excursion steamer, during the day she would take passengers on family-oriented day cruises and more adult-oriented night cruises. Admiral was a pleasure boat in the truest sense of the term and Admiral was a way for Midwesterners to relax and unwind without the travel or expense of a cruise ship. It was a unique ship whose design was birthed from a unique mind, as Admiral has the distinction of being designed by a woman, Mazie Krebbs. Admiral had equally unique owners the Streckfus Steamboat Company. John Streckfus started the company in the 1880s as a cheaper way to transport groceries from his store in Rock Island Illinois. This grew into a full-blown packet steamer company long after the golden age of Mississippi River Boats had come and passed. To keep his business going, John Streckfus developed the idea of an excursion steamer; a riverboat complete with a dance hall and live bands for people’s entertainment. In 1901 he had a ship specially constructed to incorporate all of his ideas, that was named for himself, J.S. The J.S. paved the way for excursion steamers and enjoyed a successful career until 25 June 1910 when the vessel caught fire near Victory, Wisconsin. J.S. was carrying 1,500 passengers and remarkably only three people lost their lives. Since that time, John Streckfus had the desire to build or purchase a steel-hulled vessel because the potential for a fire would be less, additionally, the US Coast Guard had developed stricter standards for wooden hulled riverboats. Having a steel-hulled excursion riverboat would not happen within his lifetime as he passed away in 1925. His eldest son Joseph took over the family business upon his father’s death and he was eventually able to build his father’s dream with both the SS President and the Admiral.

The Albatross

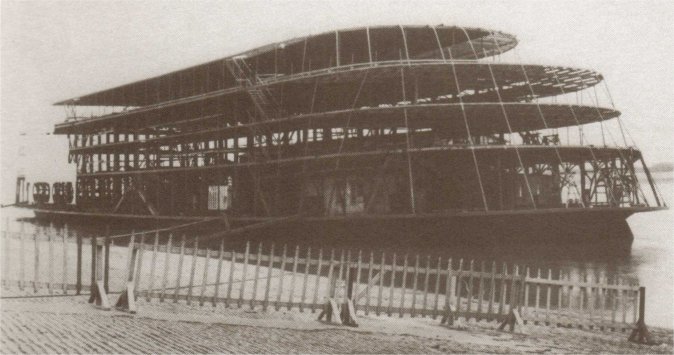

The Admiral started her life as a completely different ship, the side-wheel ferry Albatross. Built through 1906-1907 at the Dubuque Boat and Boiler Company of Dubuque, Iowa the steel-hulled Albatross was used to transport trains and railway cars for the Queen and Crescent railroad crossing between Vicksburg, Mississippi and Delta (Delta Point) Louisiana for the Louisiana and Mississippi Valley Transfer Company. Albatross was 305 feet long with a 53-foot breadth (or width) and a draft of 7.6 feet and weighed 1,103 gross tons. Above the hull, she was 90 feet wide to accommodate the side wheels. On the deck, Albatross had two rail lines for trains and could carry up to 16 railroad cars, if there were longer trains, the trains would be ferried across half at a time to the opposite shore. The deckhouses on either side held machinery, coal storage, and housing for both Albatross‘s crew and the train crews. All of her machinery was housed completely in the hull itself. Albatross was powered by high-pressure steam engines 26 inches in diameter with a 10-foot stroke. The massive Albatross was too large for the channel and to clear the bridge at Keokuk, Iowa and the entire populace of Keokuk showed up to watch the vessel shoot the rapids, which it did successfully. Albatross performed largely without incident, however in its first year of operation 28 September 1907. After dropping off passenger train No.2 from Shreveport, Louisiana, after getting up the hill in Vicksburg the dining car No.498 loosed from the train and rolled backward down the hill across the Albatross and into the Mississippi River, no lives were lost. It is unknown if the former dining car is still extant in the river. Albatross performed this duty for fourteen years with her sister ship Pelican also constructed by the Dubuque Boat and Boiler Company. In the winter of 1920-21, Albatross sailed back north to the drydocks of the Ripley Boat Company in Keokuk, Iowa to be lengthened another 57 feet thus making Albatross 365 feet long, the largest vessel to ply the Mississippi River. This was done so Albatross could carry more rail cars. The Albatross continued service until 1930 when a bridge connecting the railroads was finally constructed across the Mississippi. Without any work, Albatross was laid up until 1935 when she was purchased by the Streckfus Lines.

With his recent success with the excursion steamer President (which will be explored in a future post in the Museum Ships Series), Joseph Streckfus imagined another steel-hulled excursion steamer, the largest most modern boat on the river. With the President, Streckfus realized that it was easier and cheaper to purchase an existing ship and refit the entire superstructure rather than build a whole new ship. Albatross was the perfect candidate, being steel-hulled, stoutly built because of its job, its massive length of 365 feet, and having all of its machinery located inside of its hull.

Mazie Krebs & The SS Admiral Refit

“Old Time Rivermen must have turned over in their graves last night, for riding the river was a ship they never dreamed of – all steel, streamlined, and air-conditioned and to make it worse on the old timers, the ship was designed by a mere slip of a girl, Miss Mazie Krebs.” St. Louis Star Times 13 June 1940

Admiral has the unique distinction of being completely designed inside and out, by a woman, Mazie Krebs. Further research is required, but the SS Admiral may have the record of being the first ship designed completely by a woman. Mazie Krebs was born on 6 March 1900 in St. Louis, Missouri. Mazie was a talented artist and after high school, she received a scholarship for Graphic Design to Washington University located in St. Louis. She would teach dancing to pay for college expenses, but eventually, college got too expensive and she had to leave the university. Mazie was promptly hired as a fashion editor for the St. Louis-based Barr Department stores and eventually, she landed a job at the advertising firm of Taylor-Rebholz working as a graphic designer making large displays, outdoor posters, and billboards. Streckfus Steamers happened to be a client of Taylor-Rebholz. Krebs was in Chicago designing exhibits for the 1933 World’s Fair when she met Joseph Streckfus. Streckfus had radical ideas for a new steel-hulled steamer that eventually became the SS President and he needed someone to make those ideas a reality. Although Streckfus was a client of Taylor-Rebholz, the firm was reluctant to work on such a project in any capacity as they were an advertising firm and not shipbuilders. Steckfus wanted a ship with a cutting-edge interior, and spared no expense. Mazie was unafraid of the challenge, so she asked if she could sketch some designs for the interior, Streckfus agreed and she spent a month working on her sketches. She later returned to St. Louis to visit Streckfus at his office. Mazie had put up her sketches on a radiator and explained each to him as he listened silently, staring. His silence and lack of reaction made Mazie explain harder and she left the meeting without him ever saying a word. She had discovered later that she had sketched onto paper exactly what Streckfus had imagined for his new steamer like she had read his mind. She had also found out that her designs were accepted over the twenty firms that were competing for the design of the President‘s interior. Mazie would spend the next seven months refining her sketches and watching them come to life as the interior construction of the President was completed. The President was launched in 1934 and with its success, Joseph Streckfus approached Mazie to design another modern steamboat this time from the hull up without any competition. Mazie spent all of 1934 designing both the exterior and interior of what was going to become the SS Admiral. Streckfus lines had purchased the Albatross in 1935 but the construction on the refit did not begin in earnest until about 1937. Albatross was sailed to St. Louis and the refit was carried out at the Streckfus wharf on the St. Louis waterfront.

The rails and superstructure of the former Albatross were removed and replaced with a modern steel art deco structure. Steamer Service Company handled the construction of the Admiral and Banner Iron Works completed the steel framework for the new superstructure. During her two-year break between drawing and construction, Mazie started a syndicated comic strip named Cindy. After the exterior was completed, Mazie spent the next two years working on the Admiral‘s plush interior. The media and the locals made much speculation about the ship construction taking shape on the St. Louis waterfront, but the entire project was sworn to secrecy, Streckfus even purchased a tug the Suzie Hazard to assist with the construction of the Admiral. Steckfus had spared no expense, Admiral was five decks high, outfitted with the latest fire suppression materials, and was the first ship to be outfitted with air conditioning, a luxury in the hot Missouri summers. Very few buildings at the time had air conditioning.

When she was completed, the SS Admiral was 374 feet long and had a beam of 92 feet, making her the largest vessel to ever ply the Mississippi River. Admiral had the capacity for 4,000 passengers and was highly maneuverable with her side wheels. The only things left over from the Albatross above the hull were the bell and its steam-powered capstan (a revolving winch for winding rope or cable to lift heavy cargo). The new Admiral was painted silver and boasted a ballroom that could hold 2,000 people, a bandstand, an arcade, souvenir stands, lounges, food vendors, a cafeteria, soda fountain, bars, and four themed powder rooms each staffed with a maid. Each of the powder rooms was named for female stars of the forties. The vessel also had an Art-Deco interior to match its exterior. Admiral also boasted seventy-four compartments and reportedly as many as eleven could be flooded and the vessel could still remain afloat. Admiral also had an elevator that could ferry people to all five decks. She also had wide windows that offered views of the Mississippi River. Dining tables on the fourth deck overlooked the river and had large canvas curtains that could be drawn in wind or rain. The top deck was completely open and was where the pilothouse was located. The pilothouse also had a flying bridge that was used when docking the immense ship. Admiral was put through Sea Trials on 28 May 1940 and had its maiden voyage on 12 June 1940. Admiral was completed at a cost of $707,360.26 in 1930’s money. Mazie would be present for her creation’s maiden voyage but her career would take her elsewhere.

The Glory Days of the Admiral

Admiral would go on to entertain generations of families and many couples shared their first kiss on her decks. Admiral‘s unique appearance drew much attention Streckfus had thought outside of the box in all aspects of this vessel. Admiral was a modern vessel but still had a strong connection to the storied past of Mississippi river transport. Admiral would become part of the cultural landscape of both St. Louis and the Mississippi River. Families would flock to the vessel for the day cruises and eligible singles would flock for the evening cruises. Taking a cruise on the Admiral became a pastime, a summer tradition. She was a pleasure boat, a way for Midwesterners to relax and socialize. Advertisements for the Admiral would promise Fun! Thrills! and Romance! Admiral would offer live music for its voyages including many notable Jazz musicians of the time for the evening cruises. Other entertainments during the day trips were provided by local dance and music schools providing them an opportunity to raise funds. Later in her career Jazz and big band music would give way to rock music. On the uppermost deck or Lido deck, there was a local tour offered to identify local sites. In lieu of the menu offered on the Admiral, families were allowed to bring their own picnics aboard for their cruise. Steckfus Lines also offered group rates and rentals to various organizations for social outings. It was an honor to be a crew member aboard the Admiral and there were special initiation ceremonies held to become part of the crew. Admiral would operate in this capacity for 34 years.

In 1973-74 Admiral was repowered with diesel engines. It was apparently difficult to remove the paddlewheel shafts and each had to be cut apart and removed in sections. The two side wheels were replaced with two Murray & Tregurtha propellers each 6 feet in diameter and capable of rotating 350 degrees for maneuvering. The engines were installed within the former paddlewheel boxes with special steel mounting frames and there was a caterpillar diesel engine at the stern. The Fabick Company of Fenton, Missouri supplied all of the new propulsion machinery.

Update: Admiral’s Dark Days: The Admiral and Segregation

As mentioned in the blog post about the other historic western riverboat the SS President, Streckfus Steamers adhered to the policy of segregation, especially aboard the SS Admiral. New information has come to light and I would be remiss in my duties in sharing the history of these vessels without including this part of their history. History is plastic like that and I consider these blog posts living documents. In fact, almost all other histories and sources consulted on Streckfus Steamers, Admiral and President do not mention this aspect of their history. I said as much before in that other blog post. During most of their history Streckfus Steamers and its ships, Admiral and President adhered to policies of Segregation as was commonplace in Missouri at the time. In the blog post about the President, I stated that the history made it seem uncertain that segregation occurred on these vessels in the first place, but the new data proves that it did. On 19 May 1961, the St. Louis Board of Aldermans voted 20-4 to ban segregation at restaurants, diners, taverns, theaters, and other places of public accommodation which included both the SS Admiral and the SS President. This law is also known as the Anti-Bias or public accommodation law. Streckfus Steamers sought an injunction to prevent enforcement of the law aboard their vessels and claimed that they should be excluded from the law due to their nature of being mobile ships. Further Streckfus declared that the ordinance was unconstitutional and maintained that it would be impossible for them to summon the police in case of violence while the ships were underway. Streckfus sued in line with the other taverns and restaurants of St. Louis that sued over this law a day before it went into effect. On 1 July 1961 Eugene Davenport, his wife, two kids, and friend Sandra were the first African Americans who had attempted to get aboard the Admiral since the law went into effect. The watchstander who was also named Eugene barred their entrance aboard the steamer and informed Davenport that it “would be unsafe”. The watchstander went further and stated that he was under instruction from his employers and Captain R.M. Streckfus, head of the company confirmed that it was company policy of “continuing to refuse admission to negroes.” Regardless of the anti-bias law in effect and that denying admittance to individuals and not groups would remain as a safety measure until a settlement was reached in the court. Streckfus’s primary concern was the “rowdyism” and feared the violence that could occur aboard. It is said that Davenport did not attempt to get aboard the Admiral simply to challenge Streckfus’s policy, he honestly wanted to go aboard for an excursion with his family and was denied based on the color of his skin. It doesn’t take much to see the issues with Streckfus’s stance. A year later on 24 April, 1962 Streckfus dropped the racial ban after the city had filed a motion to dismiss its lawsuit against the City of St. Louis. The courts had contended that the vessels were common carriers in interstate commerce and prohibited by federal law from denying service on racial or religious grounds. From then on the ships of the Streckfus lines opened their doors to African Americans. The Admiral was a pleasure vessel and is remembered fondly by those who do remember, there is much nostalgia however, that nostalgia can make for a fine pair of Rose-colored glasses. So rose-colored that this part of the ship’s history is all but forgotten but it still is a part of its history and a story worth telling.

Admiral’s Latter Days

After being repowered, Admiral continued its excursions until 1979-80 when after an inspection the US Coast Guard condemned Admiral’s then 72-year-old hull. This is where Admiral‘s problems began. Streckfus Steamers had her drydocked in New Orleans, Louisiana, and had estimates made of what it would take to restore Admiral to keep her running, which rang up to the tune of $1.5 Million. Steckfus Steamers could not handle such an expensive restoration after having the vessel returned to St. Louis. Streckfus Steamers subsequently sold Admiral for $600,000 to a Pittsburg, Pennsylvania businessman named John E. Connelly, who had planned to move Admiral to Pittsburg and moored there permanently as part of his dinner cruise line Gateway Clipper Fleet Inc., which never materialized. Conelly had Admiral moved for further repairs in Kentucky. At the time there was a local uproar about St. Louis’s heritage being moved upriver. A group of local St. Louis businessmen formed Admiral Investors Inc. were able to purchase Admiral from Conelly for $1.5 Million to keep her in St. Louis but not to restore her. They then transferred ownership of Admiral to the SS Admiral Partners, which was a subsidiary of Six Flags amusement parks. Admiral was going to stay in St. Louis and continue her life as an immobile pleasure boat. During this period when Admiral’s fate was still undetermined Admiral would go through her next refit, her engines were removed, and all of the original interior along with it. Another study was conducted on Admiral that concluded Admiral should be drydocked again, this was never done. Admiral was returned to St. Louis from Kentucky and was going to be renovated into an entertainment complex with $26 Million in private and a $5 Million Urban renewal grant from the city of St. Louis. The construction company carrying out this work had no experience renovating a historic vessel, therefore, there were many delays and labor problems. This company also happened to be owned by one of the members of the SS Admiral Partners Due to this, the newest iteration of the Admiral opened a year behind schedule in 1987. They had discovered that they had to replace most of Admiral’s structural steel during the renovation further adding to the delays, which would have been easier to repair had the vessel been drydocked. This new venture had Admiral outfitted with new lounges, music venues, restaurants, a theater, a robotic band, and a disco named Vibrations. Once again, investors spared no expense in repairing Admiral to prepare her for her new life. $37 Million for the renovations, $7.5 of which were public funds. Admiral was over budget and upon opening, was not as successful as anticipated, by the eighth month of operation power to the vessel was cut off for an overdue bill of $61,000. Admiral Investors Inc. asked the city for a new loan which was refused. The food aboard Admiral was donated to charity and the doors were shuttered again. Admiral Investors Inc. was facing 270 creditors. They were able to convince former Admiral owner John E. Connelly to manage operations and add $1.5 million of his own money. Admiral reopened again in 1988 and continued to experience poor attendance. The vessel was losing money at an average of $100,000 a week and the combined forces banks and creditors threatened to foreclose on more than $10 Million in loans. After the initial acceptance, Connelly had left shortly after due to poor workmanship and irresponsible financing. By 1989 Admiral Investors had collapsed. Vincent Schoemehl the then newly re-elected mayor of St. Louis had admitted that the city’s investments into Admiral had been a mistake. Subsequently, the City of St. Louis sued S.S. Admiral partners for $209,000 in unpaid property taxes. This was quickly forgiven in exchange for the proceeds from the sale of the Admiral. Conelly had returned again and purchased Admiral for $4 Million. Conelly had a new, fresh idea for Admiral, he was going to make her into a floating casino. He had previously purchased Admiral‘s sister ship, President, and converted her into a floating casino in Davenport, Iowa. Admiral would sit unused again until Missouri State Legislature approved riverboat gambling, but they would wait until both the Iowa and Illinois state legislatures approved riverboat gambling in their states. There were several problems throughout the process of creating the law to allow for riverboat gambling and by 1994 Admiral was refit into her final role as a floating casino but without the proper referendum, the new gambling opened without slot machines and again lost most of its projected revenue and attendance. In another few months after opening the referendum was tried again and Admiral was finally allowed to have slot machines. This was not enough to keep the vessel afloat and she continued operating in the red, losing more money than it made. The owners had later attempted to sue the city of St. Louis for failing to provide adequate parking for the casino because they attributed their attendance and dwindling revenue to inadequate parking. This lawsuit failed too. On 4 April 1998 Admiral had suffered a collision with the tow barges of the MV Anne Holly. The vessel was traveling upriver towing fourteen barges when it had struck the center support for the Eads Bridge breaking off eight barges, three of which drifted into the Admiral. Admiral’s mooring lines began to snap and with all lines but two, the vessel rotated with the bow pointing downriver. Thinking quickly the captain of the Anne Holly dropped the rest of its tow and pushed the bow of his vessel into the Admiral’s bow to keep the vessel pressed up against the river bank. During this, another one of the mooring lines snapped leaving the Admiral attached to the shore by one mooring line and the pressure from the towboat Anne Holly. With Admiral at capacity with 2,500 casino patrons, 16 were hospitalized, and rescue vessels worked for hours to rescue everyone aboard. This incident reportedly caused $11 million in damages. Throughout Admiral‘s life as the floating President Casino, several attempts were made to have the vessel somewhere where it could be more profitable. This move could never be completed because the owners could not raise enough money to pay for the move and they were so deep in debt, they could never hope to raise the allotted funds. They never did and Admiral remained at her berth until the company went bankrupt in 2002. Three years later another firm, the Columbia Sussex Corp. announced that it was going to purchase Admiral and replace it with another vessel. The sale never occurred and in 2006 Pinnacle Entertainment purchased Admiral and the vessel continued operating as a casino. Pinnacle Entertainment continued to attempt to either sell Admiral or have it moved to a new location due to expensive maintenance needs, and declining business. They attempted to move Admiral upriver this time to a location north of the Chain of Rocks Bridge in 2009. This again never occurred because the State of Missouri never approved of the movement of a gambling operation or the repair/replacement of the hull. After another Coast Guard inspection Pinnacle Entertainment ended all Casino operations in June 2010. The ship was sold to St. Louis Marine and Materials and in November 2010 a final attempt was made to sell Admiral on eBay for $1.5 million, once again, there were no takers. Unable to find a buyer, St.Louis Marine held an auction to sell all of the interior fixtures. fittings and components. Scrappers began removing the interior machinery, which caused a small fire when a torch cut into a grease-filled exhaust duct in the kitchen. To make it easier to transport Admiral to her final date with the scrappers, Admiral had her uppermost deck removed to make her easier and safer to pass underneath bridges. On 19 July 2011 Admiral was towed away from St. Louis by the towboat Michael Luhr on a two-hour cruise to Luhr Brothers Inc. of Columbia, Illinois where Admiral was scrapped while still floating. The recycled material from the hull fetching $300 a ton.

Admiral and Historic Preservation

“History is not just a sequence of events, it’s an accumulation of events.” Vincent Schloemehl, former mayor of St. Louis.

It was generally agreed upon that making the Admiral into a casino would extend her life and aid in her continued preservation. In reality, it gave the ship an entirely new set of problems that ultimately led to her demise. Though Admiral continued its use as an amusement vessel, the latter attempts were to her detriment. It can be argued that Admiral‘s death knell was when she was repowered from steam to diesel. Admiral became a financial burden, a boondoggle for the city of St. Louis and the state of Missouri, bailing the vessel out time and time again. The vessel was not necessarily seen as something to be preserved, it was seen as a moneymaker that never made a return on investments. Admiral became too much of a problem, the city wanted to keep Admiral at her berth as a rightful icon to St. Louis but her owners wanted more infrastructure or moving the ship to somewhere else where it could become a profitable entity. Everyone had designs for the Admiral but none could nor wanted to address the problems with her aged hull. Admiral was used until she could not be used anymore. The fact of the matter is Admiral was gutted, nothing of her original interior remained, just her unique exterior. Admiral was literally a shell of her former self. Outside of her problematic hull and unique looks, there was nothing historically relevant anymore. Admiral had become too ingrained in gambling culture and therefore was seen as part of it and part of the problem that gambling causes. Although there were those who rallied to the old ship when she stopped operating in the 1980s, no one rallied to save the Admiral in her final days. Historic preservationists were silent, no one pursued her and there was no final campaign to save her from the breakers yard. The issues with Admiral’s 100-year-old hull were well-publicized, and it is certain that because of her hull, no one either could or would want to preserve Admiral. The decades of financial problems and use as a gambling barge had served to change the prevailing perception of the vessel, she was never really seen as a historic ship or really worth preserving. Although she was generally accepted as a St. Louis landmark and part of the city’s maritime cultural landscape. Admiral was never placed on a register of historic places on either the state or national level. Though the owners were grateful to accept historic preservation grants for the vessel’s continued upkeep, these funds were used for the upkeep and upgrade as an amusement center and not continued preservation. Her age led to her mismanagement Fortunately, many local St. Louis museums have artifacts from the Admiral on display, preserving both her history and her memory. Many people still have fond memories of the cruises they took and the times they spent on the vessel and that history will always be carried on.

Sources & Resources

Allen, Michael R. A is Not for the Admiral. Preservation Research Office

A is Not for the Admiral

Allen Michael R. S.S. Admiral on the River in the 1940’s. Preservation Research Office.

S.S. Admiral on the River in the 1940s

Allen, Michael R. State Court Ruling on the Admiral Hull. Preservation Research Office

State Court Ruling on the Admiral Hull

Allen, Michael R. Pinnacle Chief: S.S. Admiral has a Few Years Left. Preservation Research Office.

Pinnacle Chief: S.S. Admiral Has "A Few Years Left"

Allen, Michael R. S.S. Admiral offered on eBay. Preservation Research Office.

S.S. Admiral Offered on eBay

Allen, Michael R. S.S. Admiral RIP. Preservation Research Office.

S.S. Admiral, RIP

Allen Michael R. Admiral Reaping Scrap Windfall. Preservation Research Office.

Admiral Reaping Scrap Windfall

Blum, Annie. Images of America: Steamer Admiral .

Blume, Brett. St. Louis Says Bon Voyage To The SS Admiral. CBS St. Louis .

https://stlouis.cbslocal.com/2011/07/19/st-louis-says-bon-voyage-to-the-ss-admiral/

Bits and Pieces. The Admiral’s Demise.

http://bitsandpieces.us/2011/11/the-admirals-demise/

Bryant, Tim. Admiral Ships Out From St. Louis For Last Time. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Bryant, Tim. Small Crowd Watches as Admiral Leaves St. Louis. St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Bryant, Tim. Workers Prepare Admiral for a Scrap Yard. St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Built St. Louis: Crumbling Landmarks The S.S. Admiral Riverboat

https://www.builtstlouis.net/admiral01.html

Curtis, Nancy. The SS Admiral Makes its Last Voyage. St. Louis Magazine

https://www.stlmag.com/news/The-SS-Admiral-Makes-its-Last-Voyage/

Encyclopedia Dubuque. Dubuque Boat and Boilers Works

http://www.encyclopediadubuque.org/index.php?title=DUBUQUE_BOAT_AND_BOILER_WORKS

Find a Grave. Mazie G. Krebs (1900-1993)

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31416499/mazie-g.-krebs

Garrison, Chad. After 70 Years on the St. Louis Riverfront, Fate of the S.S. Admiral Could be Decided Tomorrow. The Riverfront Times.

Kansas City Times. Racial Ban Removed. 24 April 1962

Missouri Historical Society

O’neil, Tim. 60 Years Ago, St. Louis Alderman Banned Racial Discrimination in Restaurants. St. Louis Post Dispatch.

Springfield Leader and Press. Judge Weighs Racial Law. 3 July 1961

St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Streckfus Drops Discrimination Suit. 24 April 1962.

St. Louis Post Dispatch. Looking Back at the Glory Days of the Admiral.

St. Louis Post Dispatch. 5 Negroes Kept Off “Admiral” To Complain to Anti-Bias Board. 9 July 1961.

Roth, Melinda. The Albatross. River Front Times.

https://www.riverfronttimes.com/stlouis/the-albatross/Content?oid=2474396

Merkel, Jim. SS Admiral Meets Fate at Monroe County Dock.

Steamboats.org Admiral

St. Louis Today. Look Back: The Admiral’s Heydey

St. Louis Public Radio. Century-Old St. Louis Riverboat, the S.S. Admiral, being Scrapped.

Springfield News-Leader. “Admiral” to take Negroes Aboard. 24 April 1962

Umbright, Emily. The 8th U.S. Circuit Court Reverses Ruling in Runaway Barge Accident. Daily Record and Kansas City Press. Internet Wayback Machine.

Youtube. Admiral Demolition

I visited the Admiral ca. 1999 as field research for volunteer work I was doing on the equally unlucky Kalakala. I did get a tour, spoke with some of the maintenance guys and got to see the Mississippi flowing through a flooded compartment. There was an air of quiet desperation around the whole operation, casino goers included. Ols ships are expensive, as Mr. Klein said.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I apologize for the late response. That’s an fascinating insight that you have. I am planning on writing about the Kalakala in a future post. Agreed, old ships are expensive.

LikeLike